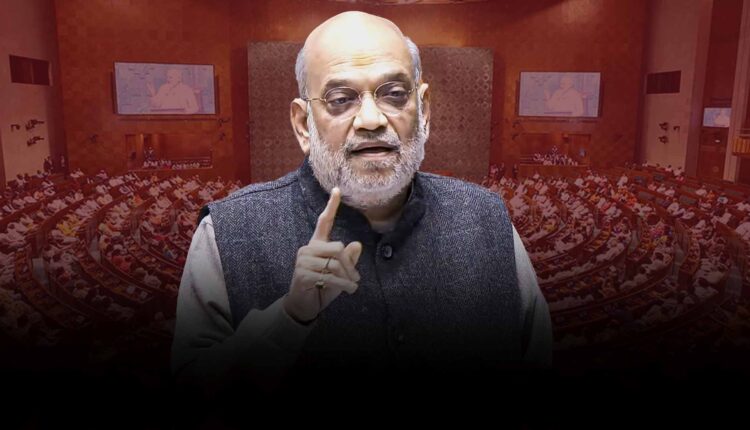

Is Amit Shah reshaping electoral reform debate with BJP’s core narrative?

The Lok Sabha debate on electoral reforms, capped by Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s reply, has sharpened political fault lines over the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls, “infiltrators” and the powers of the Election Commission of India (ECI).

While the government defended SIR as essential, the Opposition accused it of enabling a backdoor National Register of Citizens (NRC) and raised questions on data, accountability and process.

How the debate beganThe discussion on electoral reforms in the Lok Sabha concluded with Shah’s reply, and a similar debate has now begun in the Rajya Sabha, where it is expected to wrap up on Monday.

The Opposition had originally demanded a focused discussion on the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls—first carried out in Bihar before its assembly elections and now being rolled out across the country, starting with nine states and three Union Territories.

The government argued that SIR as a specific exercise could not be taken up for discussion in Parliament. In the previous Monsoon Session, this stand led to a complete washout, as the government did not concede to the opposition’s demand for a debate on SIR. The Winter Session opened in a similar fashion on December 1, with the first two days disrupted over the same issue.

Shift to broader reforms

Eventually, the government proposed a “middle path” — Parliament would not discuss SIR per se but would debate electoral reforms broadly, within which the opposition would be free to raise SIR-related concerns.

Also read: SIR debate: Amit Shah, Rahul Gandhi face off in Lok Sabha

The debate then went ahead and stretched for nearly 12 hours across two days in the Lok Sabha. A range of suggestions, charges and counter-charges were exchanged between the opposition and the treasury benches.

From the government’s side, the core arguments were summed up in Amit Shah’s reply, which is expected to form the backbone of his response in the Rajya Sabha as well.

Shah’s 3D ‘infiltrator’ formula

Shah concluded his reply by insisting that SIR is necessary and that the government would not tolerate “infiltrators” — or ghuspetiyasa term that has become frequent in the Bharatiya Janata Party’s political vocabulary.

He framed the government’s approach as a “3D formula”:

“We will detect the infiltrators, delete them from the voter lists and deport them to whichever country they have come from.”

Also read: 3 questions, 1 answer: BJP turning EC into vote-theft tool, says Rahul Gandhi

“Detect, delete, deport” — or DDD — was his closing line, presented as the core rationale for SIR and future voter-roll exercises.

This framing stands against a long-running criticism of SIR — including from petitioners before the Supreme Court — that the ECI does not have the power to verify citizenship, and that the SIR process is effectively being used to perform citizenship checks.

Backdoor NRC fears

Critics have argued that SIR amounts to a backdoor NRC, carried out surreptitiously through electoral roll revisions. The fear, particularly among opposition parties, is that the process could be used to target a large section of the Muslim population by branding them as “Bangladeshis”, “Rohingyas” or illegal infiltrators.

The Election Commission has repeatedly maintained two positions. First, that only Indian citizens can be listed as voters and it is therefore not wrong to remove non-citizens from electoral rolls. Second, that it is not conducting an NRC and is not engaged in any formal citizenship verification exercise.

Shah’s “detect, delete, deport” line brings the NRC concern back into sharp focus. If voters are being deleted for allegedly not being citizens, opponents are asking what happens to those people next — and on what evidence such decisions are made.

No clear citizenship document

The debate also highlighted the absence of a single, universally accepted citizenship document in India. During arguments in the SIR case, Aadhaar was repeatedly underlined as not being proof of citizenship.

Also read: Biggest anti-national act you can do is vote chori: Rahul in Lok Sabha

Ration cards too were flagged as unreliable. Counsel for the Centre noted that many ration cards are bogus or can be easily faked, making them unacceptable as evidence of citizenship.

Passports do serve as proof, but their penetration is low. In Bihar, passport coverage was cited as being less than 2 per cent. In that context, the opposition has asked how people can be disenfranchised on suspicion of being non-citizens when there is no robust, widely held citizenship document in place.

The infiltrator numbers question

Throughout the electoral reforms debate, opposition members pressed the government to provide data on the number of “infiltrators”, “illegal Bangladeshis” or “illegal Rohingyas” identified in the Bihar SIR.

When the Bihar SIR began, leaders including the Prime Minister, the Home Minister and several BJP figures described it as an exercise to “weed out” such infiltrators. Later, at a press conference in Patna, Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar was asked how many infiltrators had actually been found. No number was provided.

In the Lok Sabha reply as well, Shah did not specify how many infiltrators had been detected in Bihar, or in the nine states and three Union Territories where SIR is now in its final stages. Opposition members pointed out that this silence persists even as the government insists on a narrative of large-scale infiltration.

Dog-whistle politics alleged

Despite the lack of disclosed figures, several BJP and allied MPs asserted that “thousands and thousands of infiltrators” exist across the country. One of them, BJP MP Nishikant Dubey, claimed that the tribal population in Jharkhand has fallen because infiltrators have “overrun” the state and their numbers are rising while the indigenous population is declining.

Also read: Lok Sabha debate: Congress’s Tewari calls SIR ‘illegal’, demands return to ballots

This rhetoric has revived memories of earlier years of the Modi government, when the phrase “Hindu is in danger” (Hindus are in danger) was frequently circulated in political discourse.

Opposition leaders argue that the repeated use of terms like ghuspetiya and “infiltrator”, without corresponding data, serves as a dog whistle to polarise voters by creating a sense of demographic threat and fear among Hindus. They also question why, if infiltrator numbers are indeed so large, there has been no clear accounting from the ministries responsible for guarding India’s borders.

Immunity for election commissioners

Beyond SIR and infiltrators, the debate touched on several other elements of electoral reform. One key concern was the legal immunity granted to election commissioners, particularly in the context of alleged wrongdoing linked to SIR.

Congress leaders including Rahul Gandhi and Manish Tewari, Nationalist Congress Party (Sharad Pawar) MP Supriya Sule, and Trinamool Congress MP Mahua Moitra raised pointed questions on why election commissioners have been given blanket immunity from punishment for actions taken during the SIR exercise.

Shah responded that serving election commissioners could not be punished because the law provides immunity to all government servants performing official duties. He argued that:

“It is a criminal offence to obstruct a public servant from performing his duty.”

This answer was criticised as only partly addressing the issue, because the opposition’s concern was whether such immunity could become a shield for malpractice, alleged abuse or suspected wrongdoing relating to elections — areas where trust deficits already exist.

Accountability and unanswered complaints

Samajwadi Party leader Akhilesh Yadav cited multiple complaints he said he had lodged with the Election Commission regarding three by-elections.

Also read: Heated exchange in Lok Sabha over deportation of Bangla speakers

He stated that he had filed numerous affidavits putting these complaints on record, but had received no response even a year after those bypolls concluded. He questioned who would be held accountable when the Commission neither responds nor resolves such complaints.

This example was used in the debate to underline the broader concern about the lack of effective accountability mechanisms for the Election Commission within the current legal framework.

CCTV footage and 45-day limit

Another flashpoint was the issue of CCTV footage from polling stations and counting centres. Opposition parties have repeatedly demanded access to these recordings to verify the integrity of the electoral process.

Shah said that there is a statutory limitation period of 45 days after the declaration of results during which election petitions can be filed, and that the Election Commission cannot store CCTV footage indefinitely. He explained that CCTV recordings are deleted 45 days after polling, aligning with this legal window.

On this point, the opposition has also been criticised for not making full use of existing legal avenues, as there have been few election petitions filed within the 45-day period specifically demanding CCTV evidence. However, opposition leaders counter that if the Commission does not even reply to complaints for months or years, the 45-day limit becomes meaningless in practice.

A debate without closure

The overall discussion in the Lok Sabha eventually descended into a verbal duel, with allegations and counter-allegations flying from both sides and no clear answers on the key points raised.

Also read: BJP’s illegal migrant claim in Bengal falters as SIR finds few dubious entries

Fundamental questions — such as the exact number of infiltrators detected by SIR, the legal basis for citizenship verification, the design of safeguards for voters, and mechanisms for holding the Election Commission accountable — remained unresolved.

What has emerged clearly, however, is the BJP’s political line going into upcoming elections, especially in states like West Bengal, which it has described as having the “highest number of infiltrators”. The narrative of SIR as a tool to weed out infiltrators, combined with the language of demographic threat, signals a renewed emphasis on polarisation politics.

The SIR debate is therefore unlikely to end with this parliamentary session. Even if it recedes from the floor of the House, it is set to continue on the streets, among the public and in the courts, as parties and citizens contest both the process and the politics behind India’s ongoing electoral roll revision.

(The content above has been transcribed from video using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.)

Comments are closed.