Why India’s Rights Commissions are struggling to stay afloat

On paper, India’s national commissions form a dense web of safeguards. These are institutions designed to stand between the State and its most vulnerable citizens. In practice, however, many of these bodies today resemble empty shells: offices without chairpersons, commissions without members, swelling complaints and delays in placing annual reports before Parliament, raising questions about whether they can still discharge their statutory and constitutional mandates.

Across commissions tasked with protecting the rights of minorities, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, women, children, sanitation workers and backward classes, key leadership posts lie vacant.

Also read: Does VB- G RAM G just overhaul MGNREGA or dismantle rural job security? | Explained

An examination of official websites and parliamentary responses shows that several commissions are functioning far below their prescribed strength. In some, the chairperson’s post lies vacant; in others, commissions meant to have five or six members are left with one or two.

Statutory and constitutionally mandated commissions

Among the affected bodies are both statutory commissions and constitutionally mandated commissions.

The National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC), the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST), and the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) derive their authority directly from Articles 338, 338A and 338B of the Constitution.

What’s ailing India’s national commissions

Several panels are functioning far below their prescribed strength.

While one body gets constitutional elevation, parallel institutions continue to be weakened through neglect, delayed appointments and prolonged non-functioning.

The worst off are the NCM and the NCSK – both functioning without chairpersons or members.

While NCST is functioning without a vice-chairperson, the NCPCR has just one member as opposed to the mandated strength of six.

The NCBC, NCMEI have vacancies for vice-chairperson and two members, and the NCW is operating with three members instead of five.

It is said that a shortage of members increases the workload on existing members.

Another marker of institutional weakening is the delay in annual reports of various commissions.

The government knows that the easiest and most centralised way of controlling the flow of information is to make sure that there are no commissioners, said one activist.

Statutory commissions, by contrast, are created through Acts of Parliament and can be altered or dissolved through legislation. Constitutional status gives commissions a higher legal standing, defined powers and stronger institutional protection — differences that now appear increasingly consequential.

Also read: Why do people with disabilities still struggle for accessibility and representation?

When Parliament granted constitutional status to the NCBC in 2018, senior leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) hailed the move as a landmark. Prime Minister Narendra Modi too called it “a historic moment”. Critics say this chest-thumping, rooted in the BJP’s attempt to woo Other Backward Classes (OBCs) as a key votebank, stands in contrast to its record on commissions dealing with minorities and other marginalised groups.

While one body has been elevated constitutionally, parallel institutions continue to be weakened through neglect, delayed appointments and prolonged non-functioning.

Plights of minorities, safai karamcharis’ commissions

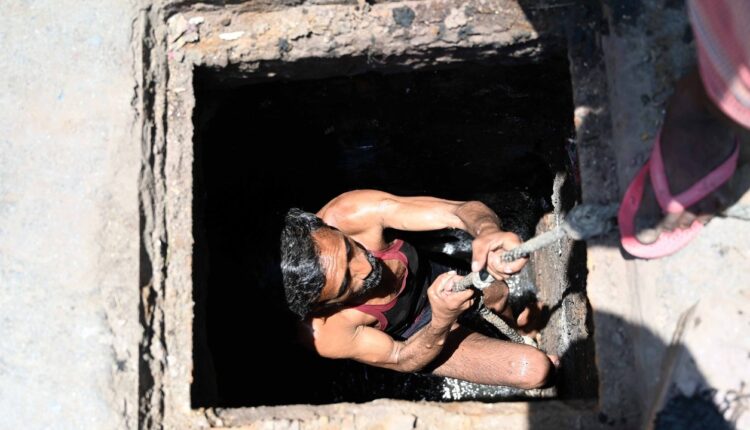

The worst off are the National Commission of Minorities (NCM) and the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis (NCSK) — both functioning without chairpersons or members, leaving their leadership entirely vacant since April 2025.

It is a political decision to destroy all the democratic institutions, and we should see this as part of that

Ironically, a parliamentary standing committee under the BJP government had once argued for strengthening the NCM. The 53rd report of the Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment, chaired by BJP leader Ramesh Bais, recommended that the NCM be given constitutional status, noting that a Bill to that effect had been pending since 2013.

“As there are various reported incidents of atrocities against the members of minority communities and the National Commission for Minorities in its present state and structure is almost ineffective in dealing with such cases of atrocities against the minorities, the Committee recommend that the National Commission for Minorities be given constitutional status as soon as possible,” the report, tabled in March 2018, said.

Also read: Constitution Day: Why November 26 demands introspection, not celebration?

Yet, far from being strengthened, the commission now lies in a shambles. A report by The Federal had shown how pending complaints from Muslim community members had shot up from just three cases in 2020-21 to 217 in 2024-25, while pendency for Christian complainants rose from zero to 42 in the same period, as the body was rendered virtually non-functional. Despite this, the government, in response to a question by Samajwadi Party MP Javed Ali Khan in Parliament on December 8, said “There is no proposal to make it (NCM) a constitutional body”.

‘No data on number of manual scavengers in India’

At the NCSK, too, work has suffered visibly. “Complaints are still being received, and those we’re dealing with more or less, but inspections have dropped sharply since the commission has been effectively empty since April. This commission was created to safeguard sanitation workers’ rights, but after all these years, we still have no data on the number of manual scavengers or rag pickers in India. There is no portal where people can lodge complaints,” an official told The Federal.

This is despite a Supreme Court order dated September 18, 2025, which stated that: “The Union, State and Union Territories are hereby directed to ensure coordination with all the commissions (NCSK, NCSC, NCST) for setting up of state level, district level committees and commissions, in a time-bound manner. Furthermore, constant monitoring of the existence of vacancies and their filling up shall take place.”

Complaints are still being received, and those we’re dealing with more or less, but inspections have dropped sharply since the commission has been effectively empty since April

The NCSK is in an especially precarious position. Its parent law — the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis Act, 1993 — lapsed in 2004, after which the body has functioned as a non-statutory commission under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.

Also read: 20 years of the RTI law: How a marquee legislation has been weakened and diluted

“With the lapsing of the Act, the Commission is acting as a non-statutory body… and its tenure is extended from time to time through government resolutions,” the NCSK website notes. The latest extension runs till March 31, 2028. Without members or leadership, however, the extension is largely symbolic.

According to Bezwada Wilson, co-founder and national convenor of the Safai Karmachari Andolan, the vacuum is a result of deliberate neglect.

Govt accused of deliberate negligence

“The government is completely purposely neglecting this. It is a political decision to destroy all the democratic institutions, and we should see this as part of that. I can say that in the case of NCSK, we have lodged complaints with them, and got no response because there is nobody there to respond. Last month, too, we submitted a complaint about septic tank deaths and got no response,” he said.

Other commissions, though not entirely headless, are also under strain. Data show that complaints at the NSCT and the National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) are also rising.

Government data tabled in Parliament shows that the NCST registered 3,592 complaints in 2024-25, up from 2,333 the previous year, and more than 2,553 in 2022-23. Pending complaints stood at 2,195 — the highest in three years — even though the commission also resolved a record 1,397 cases. The NCPCR also reported a sharp rise in cases: 12,404 in 2024-25, compared to 3,302 in 2023-24 and 2,485 the year before.

Also read: Despite decades of struggle, internal quota a distant dream for Karnataka’s Dalits

Yet in these bodies, too, key posts remain vacant. While the NCST is functioning without a vice-chairperson, the NCPCR has just one member as opposed to the mandated strength of six.

Detailed questionnaires were sent via email to the Ministry of Minority Affairs, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, the Ministry of Women and Child Development, and the Ministry of Tribal Affairs for comments, but they did not elicit a response. Emails to the NCM, NCBC, NCPCR, NCW (National Commission for Women) and NCMEI (National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions) also went unanswered. Kritika Sharma, personal secretary to the NCST chairperson, declined to comment.

First NCPCR chief calls situation ‘pathetic’

Shantha Sinha, the first NCPCR chairperson, sees the erosion as structural and the current situation as “pathetic”.

“These commissions are conscience keepers and protectors of human rights,” she said. “Each one was the result of huge politics and struggle. It is a violation of a Parliamentary Act if vacancies are not filled. I’m disappointed and also quite disillusioned that such important commissions have not been given the respect that they should have,” she told The Federal.

She added that the NCPCR, working with just one member, made it a “weak organisation”. “With more members, you distribute your function according to the area, according to subject specialisation. There are 420 million children. You can’t have one chairperson and one member looking after all of it,” Sinha said.

Also read: It’s time State Public Service Commissions cleaned up their act

Like in other cases, the NCSC has vacancies for vice-chairperson and one member, the NCBC and NCMEI have vacancies for vice-chairperson and two members, and the NCW is operating with three members instead of five.

NCSC chairperson Kishore Makwana insisted that the vacancies did not affect work. “There is no effect on the functioning… Not even one per cent. In fact, we’re doing more work than before,” he told this publication. While officials at the commission agreed, they also said that the burden of approximately 50,000-55,000 active pending complaints and other work increased the load on existing members.

“Appointing people is a government decision; we have no role to play in it. Our work is not stopping. The workload has been divided by the existing commission, so they have more work. The number of hearings and visits has increased for some people,” he said.

In the case of NCBC, the government said in a Parliament answer on August 19 this year that “no investigation is pending as on date” — an implausible scenario.

Delay in panels’ annual reports

Another marker of institutional weakening is the delay in annual reports of various commissions — one of the primary mechanisms through which Parliament reviews their functioning. On the NCM website, the last annual report is for 2010-11. No other public information is available on the latest report. The NCSK website also shows the last report for 2021-22. In the case of NCST, the last five reports are yet to be laid in Parliament.

Also read: How Kerala’s empowerment programmes are ensuring women’s participation in grassroots politics

A similar pattern has played out in other statutory bodies tasked with enforcing transparency and accountability.

The case of CIC

Recently, the government was forced to make appointments to the Central Information Commission (CIC) after prolonged and repeated periods of vacancy that had severely crippled its functioning. The appointments were made only after sustained litigation by activists and repeated interventions by the Supreme Court, which pulled up the Union government for failing to fill vacancies and directed it to ensure the commission functioned at full strength.

Activists and petitioners have argued that without judicial pressure, the government showed little urgency in restoring the statutory body responsible for enforcing the Right to Information Act.

The current government, in a way, hates rights. They’re happy giving charity (daan), but not rights… This government has, very bluntly, weakened the organisations that represent their own people

“The way we understand this is that it is a very deliberate move. The government has realised that the best way to scuttle accountability is by not ensuring that appointments are made to institutions of transparency and accountability. The RTI law clearly provides that if the government does not give information, the second appeal or complaint lies with the information commission. That is why the commission is such a crucial institution in the accountability framework,” said activist Anjali Bhardwaj, whose case against vacancies in the CIC is currently ongoing in the apex court.

Also read: Why law banning commercial surrogacy has landed women who rented their wombs in greater misery

“Very often, both at the Centre and in the state information commissions, commissioners order disclosure of information that governments find uncomfortable. These orders go directly against the interests of those in power. For instance, in the Modi degree case or the names of loan defaulters of public sector banks. The government has realised that the easiest and most centralised way of controlling the flow of information is to make sure that there are no commissioners. As a result, commissions are either left vacant or are made to function at a severely reduced capacity,” she added.

More cases going to courts

Like in the case of CIC, as national commissions falter, complainants are increasingly turning to courts. Among them is Mujahid Nafees, convenor of the Minority Coordination Committee, who has raised the matter of vacancies in the NCM in the Delhi High Court.

Also read: Haryana’s ‘killer mom’ case: Why it’s wrong to link violence by women to vanity, envy

His plea describes the commission as having undergone a “complete and systematic incapacitation”, rendering it “entirely defunct and headless”.

On Nafees’ plea, the Delhi HC had in October asked the Centre for a response. The next hearing is scheduled on January 30.

‘Govt hates rights’

“This current government, in a way, hates rights. They’re happy giving charity (daan), but not rights… This government has, very bluntly, weakened the organisations that represent their own people: keeping all the commissions vacant, not appointing them for years, and even if they are appointed, appointing their own party post holders,” said Nafees.

“The justice system in our country is very long and expensive. These commissions were formed so that deprived sections of this country could file their complaints without a lawyer, on the basis of a simple application, in front of the commission that represents their community. Today, even that door is closed,” he said.

Comments are closed.