Indian scientists develop non-invasive method to measure quantum atom density

Indian researchers at Raman Research Institute (RRI) have discovered a gentler alternative to peering into the quantum realm, enabling them to feel how densely the atoms are packed without disturbing the delicate situations that make quantum materials so unique.

This new approach offers a unique set of properties to researchers in experimental physics such as high accuracy, real-time measurement, and low disturbances. It might become a fundamental helpmate on the path of quantum computing and quantum sensing from theory to practical implementation.

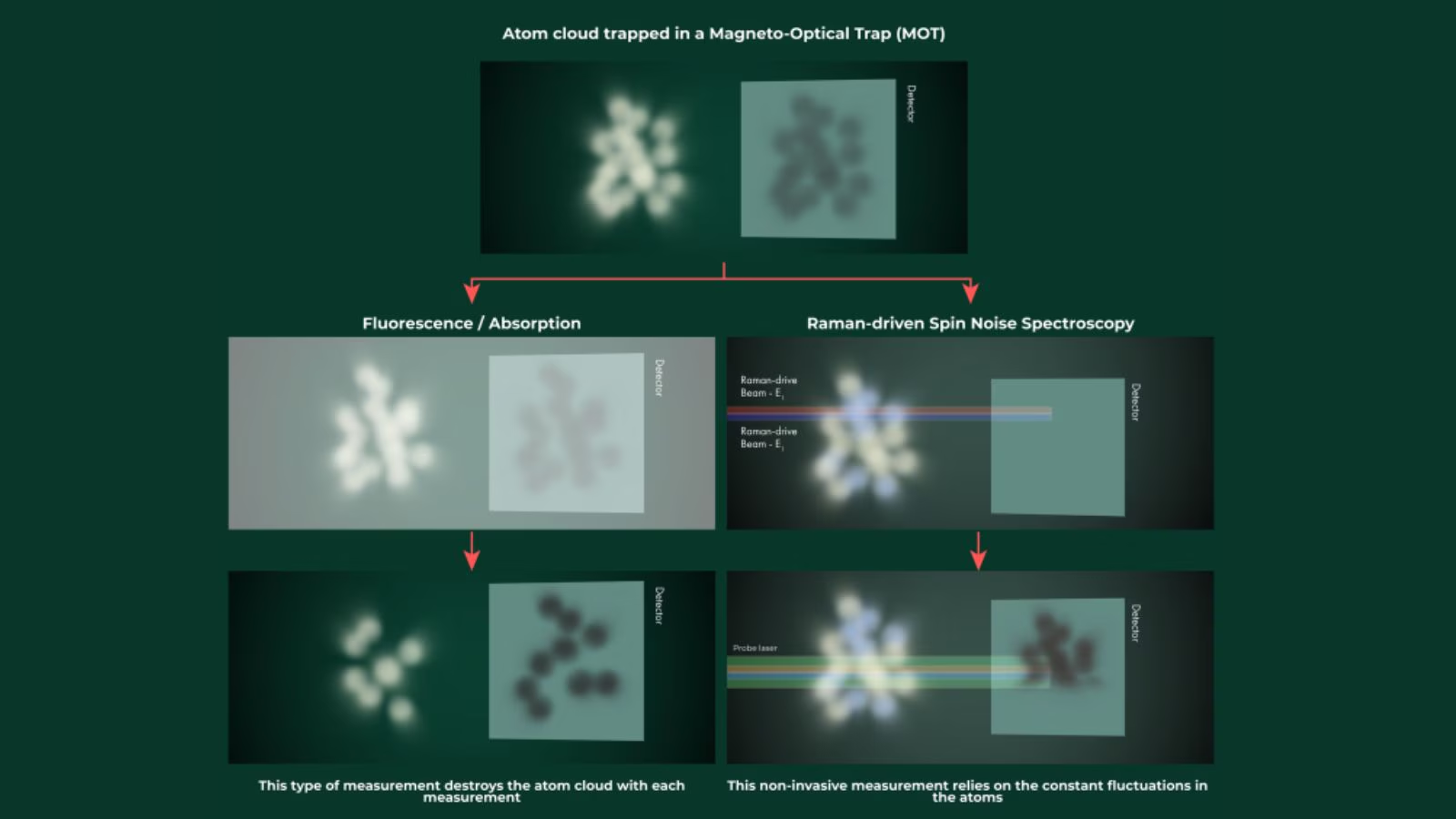

Present-day quantum experiments may employ clouds of atoms which are refrigerated to temperatures near absolute zero. In this extreme environment, atoms move slowly enough to exhibit quantum properties to a degree amenable to uses in systems related to neutral-atom quantum computers or ultra-sensitive sensors. However, observing atoms has always posed a problem. The very act of measurement can heat the atoms, scatter them, or push them out of the delicate quantum states researchers want to study.

Conventional imaging methods highlight this problem. Absorption imaging can fail when atomic clouds become dense, because the probing light struggles to pass through the cloud uniformly. Although fluorescence imaging is sometimes more reliable, it usually requires longer exposure times and stronger light, which can disrupt or even destroy the atoms’ quantum state. In fast-moving or tightly confined systems, these drawbacks become especially limiting.

Researchers at RRI have now shown that it does not have to be this way. They have demonstrated a technique known as Raman Driven Spin Noise Spectroscopy, or RDSNS, that can extract local density information from cold atoms while leaving the system largely untouched. Instead of forcing atoms to respond strongly to light, the method listens to what the atoms are already doing.

At its core, RDSNS detects tiny, natural fluctuations in the spins of atoms. As a weak laser beam passes through the atomic cloud, these fluctuations subtly change the polarisation of the light. By carefully analysing those changes, scientists can infer properties of the atoms without directly perturbing them. The RRI team enhanced this signal by using two additional laser beams to gently drive atoms between neighbouring spin states, boosting the detectable signal by nearly a million times.

This amplification makes it possible to zoom in on an exceptionally small region of the atom cloud. By focusing the probe beam to a width of just 38 micrometres, the researchers examined a volume of about 0.01 cubic millimetres containing roughly 10,000 atoms. Rather than reporting a single number for the entire cloud, the technique reveals how densely atoms are packed at that precise location.

When the team applied RDSNS to potassium atoms held in a magneto-optical trap, an interesting picture emerged. The density at the centre of the cloud reached its maximum within about one second. In contrast, measurements based on fluorescence showed that the total number of atoms continued to rise for nearly twice as long. The finding illustrates a subtle but important point: global measurements can miss local dynamics that unfold much faster and carry critical information.

Because the probing light used in RDSNS is far from the atoms’ natural resonance and kept at low power, the method is effectively non-invasive. It can deliver reliable results even on microsecond timescales, making it suitable for tracking rapid changes inside quantum systems. To check its accuracy, the team compared RDSNS data with density profiles derived from fluorescence images using mathematical reconstruction techniques. The close agreement confirmed that the new approach is both precise and dependable, while also working in situations where traditional assumptions, such as perfect symmetry, break down.

The implications of the research may be extensive. Much of the quantum gadgetry, such as gravimeters and magnetometers, operates because it knows the density of the atoms. In fact, the approach presented here may provide a way to experimentally study the transport properties of quantum matter because it now has the sensitivity to examine the density fluctuations.

Support for this research, led by India’s National Quantum Mission, demonstrates the importance of a straightforward but potent concept: sometimes, in order to properly comprehend the quantum realm, the best course is not to peer deeper but to peer softly.

Comments are closed.