What Polish filmmaker Andrzej Wajda’s cinema teaches India about censorship

The 17th edition of the Bengaluru International Film Festival (BIFFes), set to be held from January 29 to February 2, will mark the centenary year of celebrated Polish filmmaker Andrzej Wajda — a central figure of the Polish Film School whose work profoundly shaped post-World War II European cinema — through a retrospective of his landmark films. “Cine enthusiasts can experience the best of Andrzej Wajda, especially The Promised Land, The Maids of Wilko, Man of Iron and Katyn,” said P B Murali, Artistic Director of BIFFes.

“Wajda belongs to that rare lineage of filmmakers for whom cinema was not entertainment, or even an aesthetic exercise alone, but a moral responsibility — a space where history is contested and memory reclaimed. In this sense, Wajda (1926-2016) stands close to some of India’s most important filmmakers: Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, Shyam Benegal, Girish Karnad and, more recently, Shaji N Karun. That is why the 17th edition is marking Wajda’s centenary by screening his films for the benefit of those who love moving visuals and create meaning through their movement, in the Retrospective category,” Murali told The Federal in an exclusive conversation.

A champion of human dignity, freedom

At a moment when cultural expression is increasingly policed — sometimes by the state, sometimes by mobs, and often by self-censorship disguised as prudence — Wajda’s cinema offers a sobering lesson. He reminds us that the most dangerous censorship is not the ban or the cut, but the slow normalisation of silence, where artists begin to anticipate punishment and adjust their vision accordingly. To return to Wajda today is not an act of nostalgia, but an act of vigilance.

Also read: Shaji N. Karun: Cinematographer-auteur who introduced a new visual poetics to Indian Cinema

Wajda experienced the Nazi invasion as a teenager and joined the anti-Nazi resistance at 16, experiences that influenced his cinema. After the war, he studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków and later film directing at the Leon Schiller State Theatre and Film School in Łódź. He rose to prominence in the late 1950s with his resistance trilogy — A Generation, Channel and Ashes and Diamonds — which explored moral conflict, survival and disillusionment in wartime and post-war Poland. Ashes and Diamonds earned international acclaim, including the Critics’ Prize at the Venice International Film Festival.

Across a prolific career, Wajda combined historical reflection, political critique and lyrical humanism in films such as The Birch Wood, The Promised Land, Man of Marble, Man of Iron and Danton. His work consistently championed human dignity, freedom and moral courage. Beyond cinema, he was also a celebrated theatre director and a major cultural figure in Poland and abroad.

The year of Andrzej Wajda

In the history of world cinema, Wajda stands as one of the most morally engaged filmmakers. His cinema is inseparable from Poland’s turbulent twentieth-century history, yet it transcends national boundaries through its insistence on ethical inquiry, historical reckoning and artistic freedom. He persistently asked how truth survives amid ideological coercion, political violence and collective amnesia. His artistic temperament was forged in trauma, as part of a generation seeking new cinematic languages to articulate post-war disillusionment.

Also read: Girish Kasaravalli interview: ‘I didn’t have the mental make-up for mainstream cinema’

Poland is honouring a range of cultural and historical figures, including Oscar-winning Wajda, under a resolution adopted by the Senate, the Upper House of Parliament. The year 2026 marks the centenary of Wajda’s birth and the tenth anniversary of his death. Programmes organised by the Polish government will provide an opportunity to revisit his body of work, widely described as a cornerstone of Poland’s cultural heritage. Wajda’s films explored wartime and post-World War II experiences, as well as the moral and political dilemmas of later decades. Both the Polish Senate and international cultural institutions have declared 2026 the official ‘Year of Andrzej Wajda’ to honour his contribution to cinema and Polish history.

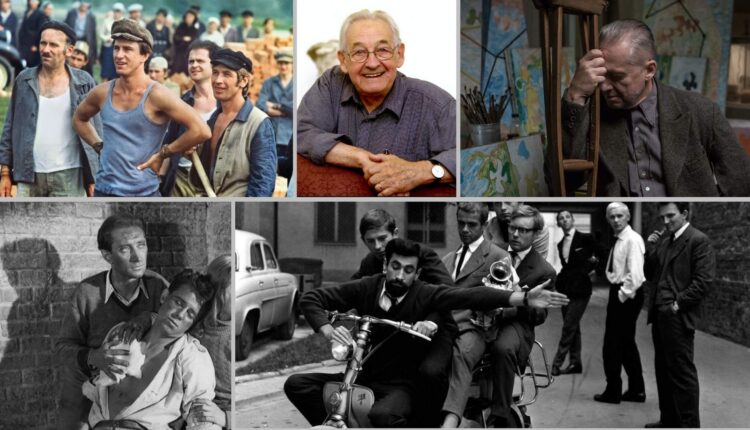

A still from The Promised Land

Wajda received the most prestigious film awards, including an Oscar from the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Palme d’Or at Cannes, the Golden Lion at Venice, the Golden Bear at Berlin, the British BAFTA, the César and the Félix for Lifetime Achievement. The 24th Kinoteka Polish Film Festival is also featuring an expansive Wajda retrospective as its centrepiece, with screenings of his films and discussions on their themes and legacy.

Taking moral positions in films

Cinephiles recognise Wajda not only for his craft, but for his role as a custodian of historical memory. His legacy lies in demonstrating that cinema can be both national and universal, political and poetic. In an era increasingly dominated by spectacle and algorithm-driven storytelling, Wajda’s work reminds us that cinema’s highest calling may be its capacity to bear witness, to confront uncomfortable truths, and to preserve moral complexity against the pressures of power and forgetting. Wajda’s films moved fluidly between realism and symbolism, intimacy and spectacle, historical epic and chamber drama. His painterly compositions, expressive use of colour and theatrical blocking reveal a director who believed that form itself could carry ethical meaning.

A still from The Maids of Wilko

Wajda is particularly known for taking clear moral positions in his films and for arguing that art must choose sides, especially ethical ones. It can be confidently said that Wajda belongs to a global fraternity of filmmakers who understood that history without ethics becomes propaganda, and art without courage becomes decoration. His films remind Indian viewers that the struggle between state power and individual conscience is not geographically bound — it is perennial. Wajda’s cinema functions as a form of moral memory, resisting both state-sponsored amnesia and the seductions of myth.

Appreciating BIFFes’ initiative to hold a retrospective of Wajda’s films at its 17th edition, N Vidyashankar, cultural and film critic and a member of The International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI), told The Federal: “A retrospective of Wajda assumes significance in the broader cultural framework of the global social and political scenario, as Wajda’s cinema offers sustained reflections on resistance, protest and the role of art during periods of historical trauma brought about by political violence, irrespective of the ideological justifications advanced by those in power.”

Control over cultural instruments by state power

Taking a clinical view of how emerging technologies consolidate political and economic orders through cinema, television and digital media, Vidyashankar observed: “Contemporary global politics presents a familiar paradox in modern Western civilisation, with its long history of colonisation and imperial power, continuing to operate under the ideological garb of democracy, liberalisation, globalisation and privatisation, with little respect for ethical questions of distribution, equality or empathy. The Eastern Bloc, often masked as socialism, advances a strikingly similar agenda in the name of progress. A retrospective of Wajda gains importance in this socio-political ecosystem, which remains trapped in the illusion of the market economy.”

Also read: Ikkis review: Dharmendra’s final bow, Agastya Nanda lift Sriram Raghavan’s anti-war film

Labelling Wajda an enduring central cultural figure of this historical moment, Vidyashankar added: “Through allegory, symbolism and direct historical engagement, Wajda’s films influenced and connected contemporaries such as Krzysztof Kieślowski and Krzysztof Zanussi, among many others, shaping a collective fight for artistic freedom.”

When this writer met Zanussi during his visit to Bengaluru to participate in the 11th edition of BIFFes, the conversation turned to Polish cinema and Wajda’s legacy. Handing over a signed copy of Time to Die — his memoir published in 1999, reflecting on artistic dilemmas and life under totalitarianism — Zanussi described Wajda as his “real mentor and a real genius of cinema.” He acknowledged Wajda’s profound influence on his filmmaking and spoke of their shared involvement in the ‘cinema of moral concern’ movement, as well as their solidarity against communist authorities.

Recalling how Wajda once jokingly called him an “idiot” for changing the ending of Family Life — a remark that showed their closeness — Zanussi said, “Wajda’s direct involvement is there in my work.” He did not forget to acknowledge Wajda as his mentor. Noting that both were deeply engaged in the cinema of moral concern, Zanussi traced the common ground between Wajda’s Man of Marble and his own Camouflagedescribing them as films “from the same bag and of the same type.”

Comments are closed.