Illegal leak, copyright violation, or coercion? Experts explain

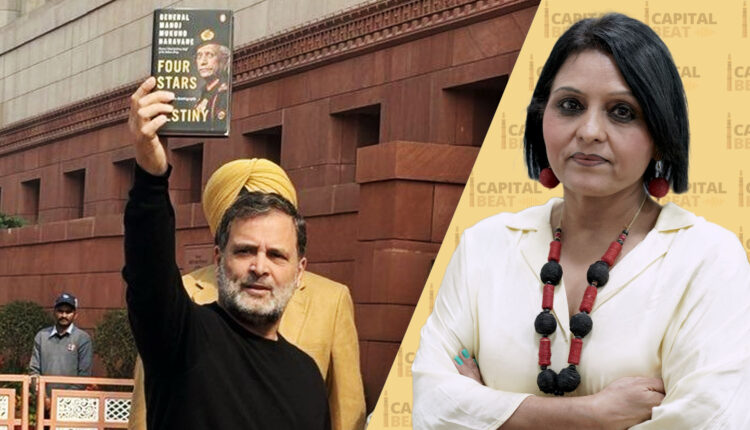

A political and institutional storm has erupted over former Army Chief General Manoj Mukund Naravane’s memoir Four Stars of Destiny. The Federal spoke to senior journalist and political commentator Saba Naqvi, author and policy expert Pushpraj Deshpande, and independent security expert Lt Gen Ashok K. Mehta (Retd) on Capital Beat to unpack the escalating row over the unpublished memoir and the implications for India’s democratic discourse.

Also read: As MM Naravane’s memoir sparks interest, his thriller makes it to Amazon bestseller lists

As questions swirl over leaked excerpts, pre-orders, and a sudden police FIR, the controversy has raised deeper concerns about free speech, military transparency, and the role of publishers under political pressure.

FIR and denial

The controversy intensified after Delhi Police’s Special Cell registered an FIR over the alleged circulation of an unauthorised version of General Naravane’s book. Soon after, Penguin Random House India issued a clarification stating that the book had not been published in any form — print or digital — and that no copies had been distributed or sold.

However, this clarification was immediately questioned when an old social media post by General Naravane from December 15, 2023, resurfaced. The post stated that the book was “available now”, tagging Penguin India and sharing a purchase link. Congress leader Rahul Gandhi cited the post publicly, asking whether the former Army Chief or the publisher was lying.

The apparent contradiction between Penguin’s denial and the earlier promotional material became the central flashpoint of the debate.

Pre-order puzzle

Author Deshpande explained that the confusion stemmed from a lack of public understanding of publishing practices. He said that once a book is announced and put up for pre-order, publishers routinely send advance manuscript copies — clearly marked “not for circulation” — to journalists, reviewers, and influencers to generate buzz.

According to Deshpande, it is standard for 100-200 such copies to circulate ahead of publication. Excerpts often appear in the media during this phase, even though the book is not yet available at retail outlets.

He argued that Penguin’s own “quick guide” to publishing — shared during the show — made it clear that a book announced or available for pre-order is not the same as a published book.

Due diligence question

Deshpande stressed that legal and regulatory compliance is the publisher’s responsibility, not the author’s. If any government clearance was required, he said, it should have been obtained before the book was even offered for pre-order.

“If there was a requirement for Ministry of Defence clearance and Penguin did not do that, that failure is entirely on the publisher,” he said, adding that neither the author nor the Opposition could be blamed for discussing excerpts that were already circulating.

He suggested that Penguin may have withdrawn the book after a “retrospective order” from the government, something that could only have come from the highest levels of power.

Commercial silence

A recurring question raised by Deshpande was why Penguin was not capitalising on the controversy surrounding what could be one of the year’s biggest non-fiction releases.

“Any publishing house is ultimately a business,” he said. “Why is Penguin behaving like a publishing arm of the Government of India instead of a commercial establishment?”

He argued that the publisher’s silence and retreat suggested pressure rather than a neutral legal decision, especially given the scale of public interest generated by the controversy.

Penguin’s track record

Naqvi contextualised Penguin’s response by pointing to its history. Having published with multiple houses — including Rupa, Westland, and Penguin — she said Penguin was a large, commercially cautious publisher that subjected all political manuscripts to extensive legal vetting.

She noted that Penguin publishes books favourable to the ruling establishment, including Exam Warriors by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, while also having previously withdrawn Wendy Doniger’s book under pressure.

“Penguin is not considered the most courageous publisher,” Naqvi said, “but it is the biggest. It has market reach, and it is extremely careful.”

In her view, it was implausible that Penguin would have moved forward with a former Army Chief’s memoir without some form of clearance already in place.

Who leaked it?

Naqvi said that if authorities pursued the FIR seriously, it could lead to widespread scrutiny of journalists and media professionals who routinely receive advance copies.

“You would be arresting half the media of Delhi,” she said, noting that manuscripts are often shared over email and WhatsApp during pre-publicity phases.

She questioned whether the investigation would genuinely seek the source of the leak or merely serve as a warning signal to suppress further discussion.

Military clearance

Lt Gen Mehta (Retd) provided a critical institutional perspective, stating that even retired officers remain bound by the Official Secrets Act and service rules.

He argued that there was “no way” a former Army Chief could have sent a manuscript to a publisher without military intelligence clearance, which falls under the Ministry of Defence.

His assessment was that Penguin would not have proceeded with pre-orders or excerpts unless such clearance had already been granted.

What triggered panic

Lt Gen Mehta suggested the government’s concern arose only after specific excerpts were reported in the media, particularly those related to Agnipath and Operation Snow Leopard.

He argued that once these passages became public, the government moved swiftly to halt the book because it portrayed decision-making during the China standoff in an unfavourable light.

According to him, the government routinely invokes “national security” selectively — publicising military actions when they suit its narrative, while suppressing discussion when they expose strategic failures.

Debate denied

All three panellists agreed that the core issue was not copyright infringement but the suppression of debate.

Deshpande said the Opposition was doing its job by raising questions based on excerpts already in circulation, while Naqvi warned that the case set a dangerous precedent for authors and publishers alike.

Lt Gen Mehta concluded that the book would likely never be officially released unless there was a change in government, though its key arguments were already in the public domain.

“The book doesn’t need to be published anymore,” he said. “Everyone already knows its essence.”

A chilling signal

As the investigation continues, the controversy has exposed fault lines between national security, political accountability, and freedom of expression. For authors, publishers, and former officials alike, the Naravane episode has become a cautionary tale of how power, pressure, and publishing intersect in contemporary India.

(The content above has been transcribed from video using a fine-tuned AI model. To ensure accuracy, quality, and editorial integrity, we employ a Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) process. While AI assists in creating the initial draft, our experienced editorial team carefully reviews, edits, and refines the content before publication. At The Federal, we combine the efficiency of AI with the expertise of human editors to deliver reliable and insightful journalism.)

Comments are closed.