After Indus Waters, Is It Time For India To Rethink The Farakka Treaty With Bangladesh? , Analysis India News

India’s decision to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan after the Pahalgam terror attack in 2025 has reopened a larger debate in New Delhi: should decades-old water-sharing arrangements continue unchanged when geopolitical realities and domestic needs have fundamentally shifted? Against this backdrop, the Bharat–Bangladesh Farakka Water Treaty, signed in 1996, has come under renewed scrutiny—especially amid rising anti-India rhetoric from sections of Bangladesh’s political establishment.

A Treatise Born in a Different Era

The Farakka Water Treaty was crafted during a phase of relative warmth in India–Bangladesh relations. Both sides sought to resolve long-standing disputes over the Farakka Barrage, constructed by India to divert Ganga waters into the Hooghly River to sustain Kolkata Port. For Bangladesh, the treaty was both a reassurance and a safeguard—ensuring that upstream India would not deny dry-season water critical for agriculture, fisheries, and livelihoods.

Add Zee News as a Preferred Source

The agreement laid down a detailed allocation schedule from January to May, dividing water flows every ten days. When flows exceed 70,000 cusecs, Bangladesh is guaranteed 35,000 cusecs, with India receiving the remainder. When flows dip below that threshold, the waters are shared equally. However, the treaty contains a glaring weakness: it offers no minimum guaranteed flow during extreme droughts, mandating only “emergency consultations” if levels fall below 50,000 cusecs.

Changing Realities, Rising Frictions

While the arrangement functioned for years, stress fractures are now visible. Bangladesh has repeatedly accused India of withholding water during peak agricultural months, particularly March and April—claims backed by multiple flow assessments over the past two decades. Conversely, India argues that the agreement has become increasingly inequitable.

The treaty was based on river flow data from 1949 to 1988—figures that no longer reflect today’s hydro-climatic realities. Erratic monsoons, Himalayan glacial retreat, and rising consumption have dramatically altered the Ganga’s behaviour. On both sides of the border, water demand has nearly doubled, with Indian states like West Bengal and Bihar facing acute water stress.

Leverage, Diplomacy, and Strategic Signaling

With the treaty set to expire in 2026, New Delhi is reportedly considering a shorter renewal of 10–15 years instead of another 30-year term. The logic is clear: flexibility is essential in an era of climate uncertainty and heightened geopolitical competition.

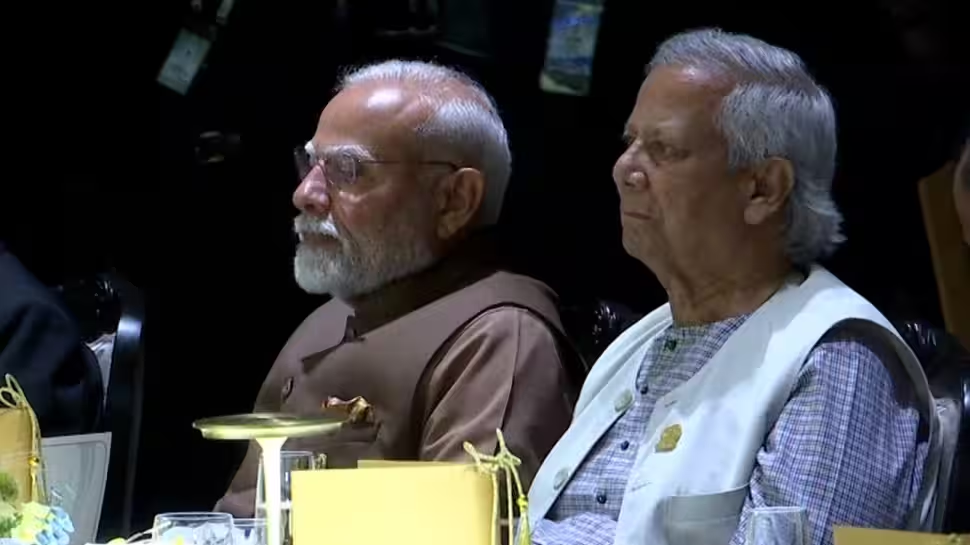

Reports claim that India has informed Dhaka of its need for 30,000+ additional cusecs to meet developmental and agricultural requirements, marking a significant shift. Such a demand would inevitably reduce Bangladesh’s share, affecting its agriculture and industry—something that could force Dhaka’s interim leadership under Muhammad Yunus to reassess its political messaging and diplomatic posture toward India.

The message from Delhi is increasingly unmistakable—water diplomacy, like security cooperation, cannot be insulated from broader bilateral conduct. In a region where goodwill cannot be taken for granted, India appears ready to recalibrate agreements to reflect both national interest and changing ground realities.

Comments are closed.