How Aditya Dhar’s lavish spy thriller pushes nationalist propaganda

The noise around Aditya Dhar’s Dhurandhar, which has the entire country raving and ranting, refuses to die down even three weeks after its release. If critics have been unequivocal in seeing the film for what it’s, praise, too, has arrived thick and fast for the lavish spy thriller which looks set to enter the coveted Rs 1000-crore club. It has spawned thousands of spy memes and reels on social media, and is being variously described as ‘seminal,’ a ‘quantum leap’ for Indian cinema, and ‘the most patriotic film.’ However, if you have watched how a section of Hindi filmmakers has grown increasingly eager to push the narrative of the BJP government at the Centre over the past decade, the avalanche of unqualified applause for this film is difficult to take at face value. For anyone paying attention to this drift and capitulation, it is amusing and even absurd.

The film’s defenders have gone hammer and tongs at its critics, with many trolls reserving a fusillade of abuse for those who have pointed out its flaws, including its apparent ideological embeddedness. But even those who are heaping high praise on the film can’t deny that it panders to the prevailing political mood and seeks to exploit to the hilt the climate of anti-Pakistan rhetoric, assured in the knowledge that it’s a sure-shot way to rake in big bucks at the box-office. Curiously, one notices a deliberate evasion at the heart of the defence mounted for the film, the insistence that calling it ‘a propaganda film’ steeped in the line of the state is an insult to its craft. It is not.

A twist of irony

Dhurandhar is, inarguably, a propaganda film because it has been made with a clear intent: to burnish the image of the ruling regime while reducing Pakistan to a permanent, one-note antagonist neighbour invested solely in the manufacture of terror. Because it appropriates real events, real locations, and real people, and then aligns them to a spin that serves the Centre’s political interests. The film reveals its intention early on. Its opening reconstruction of the IC-814 hijacking aftermath sees R. Madhavan’s Ajay Sanyal, modelled on National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, entering the scene, to negotiate with the gun-toting terrorists. He addresses the dazed, battered hostages with a rhetorical flourish — the call to “Bharat Mata ki…” — that is greeted not with “Jai” — as he desperately wants them to — but stunned silence since the terrorists have their guns trained on them.

That moment establishes that the film is going to be in the mould of its many predecessors that have cashed in on such moments to whip up jingoistic frenzy. The opening sequence, with flashes of gore, brutality and bloodshed, works as psychological priming, preparing the viewer to get into the mode for revenge. The film uses it as a cue: a moment of wounded national pride, waiting to be answered with vengeance, with all the force, technology, and intelligence know-how it can muster. Failed by the higher-ups in Delhi who decide instead to release some terrorists, Sanyal proposes a long-term plan to infiltrate Pakistan’s terror networks — codenamed Operation Dhurandhar — awaiting for a leader who will ‘care’ for his country to execute it. No points for guessing who that leader is.

From there, Dhurandhar moves across a decade of Indo-Pakistan conflict — IC-814, the Parliament attack, 26/11 — treating these episodes as pit stops to build the larger arc that shows Pakistan as an out-and-out evil, exporting terror across the border. It borrows heavily from real events but also has the tag of fiction to retreat into when confronted with questions about accountability when it comes to what it overtly and covertly depicts. This selective realism is a political choice. It is visible in the film’s portrayal of Karachi, especially its town Lyari, a historically Baloch, working-class neighbourhood, which is shown as merely as a nursery for gang wars, with not even a glimpse of its rich musical legacy or its identity as Pakistan’s football capital that has earned the nickname of “mini Brazil.”

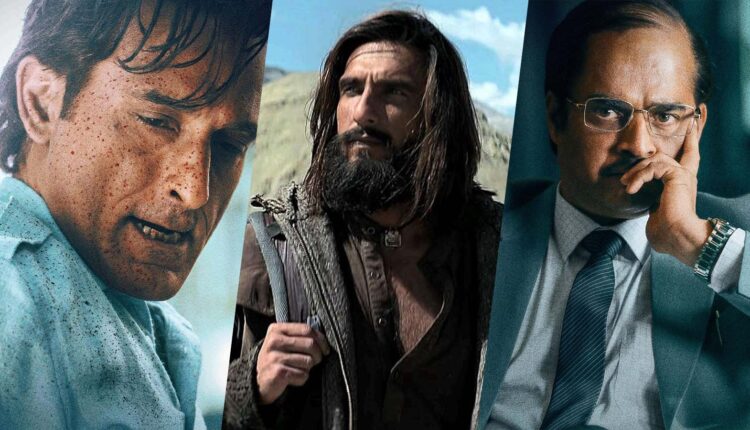

Also read: Dhurandhar review: Ranveer Singh’s tall act barely salvages the shallow spy thriller

The film seeks to lionise Sanyal aka Doval and his man in the “land of Muslims”, but in an ironical twist, much of the film’s traction and buzz have been centred not on its righteous Indian spy (Ranveer Singh) but on the very figure it seeks to demonise: Rahman Dakait (Akshaye Khanna) whose methodical performance has stolen the thunder from the mail lead. The character, modelled loosely on the real Lyari gang leader, was clearly designed as proof of how deeply India’s intelligence has “penetrated” Pakistan’s terror ecosystem. But people seem to have responded less to the triumph of infiltration than to Dakait himself: his aura and coolness quotient. Clips, dialogues, and even the song — FA9LA by Bahraini rapper Flipperachi, which has taken a life of its own — filmed on Khanna in dark glasses, doing his distinctive dance move, have travelled widely, overshadowing the ostensible hero. If Dhurandhar does end up as the year’s biggest commercial success, it will owe no small part of that success to its villain.

The politicisation of cinema

The pattern we see in Bollywood today has precedent in Hollywood. Films like Zero Dark Thirty, American Sniperand the Top Gun: Maverick have all been read — rightly — as state-backed projects to push certain theories. If Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty (based on the decade-long hunt for Osama bin Laden) normalises torture as a necessary evil, Clint Eastwood’s American Sniperan adaptation of the autobiography of Chris Kyle, a Navy SEAL sniper, allegedly the most lethal in US military history, reduces war to be a White man’s trauma and demonises Iraqi civilians. Top Gun: Maverick, made in collaboration with the Pentagon, portrays a positive image of US military power, nationalism, and American exceptionalism, steering clear of the realities of the war.

While in the US, films like these are argued over, picked apart, mocked, challenged across mainstream media platforms, in India, criticism of such films are not without risks; a cabal is always ready to pounce on you. The lines between state messaging, mass media, and storytelling through films have blurred so much that it leaves little room for dissent to travel without friction and fracas. As it has happened in the case of Dhurandhar, which follows Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019), Dhar’s debut, which established a commercially and culturally potent model for ‘national security cinema’. Uri was widely praised for its technical work and energy. It was also released at a politically charged moment (the general elections were around the corner) and its framing of military action as moral inevitability dovetailed seamlessly with official rhetoric.

Dhurandhar refines that formula. If Uri was openly rousing, Dhurandhar is a bit restrained. If Uri featured provocative dialogues (‘unhe Kashmir chahiye, humein unka sar; they want Kashmir, and we their heads’) Dhurandhar by and large abstains from incendiary stuff, except from a few things here and there, including the crude and coarse line in the end: “This is the new Hindustan. He will enter the house and will also kill. / This is the new India. It will enter your home, and it will kill.” The line, borrowed from PM Narendra Modi’s speech, turns state aggression as a badge of moral and tactical superiority.

But the ideological architecture of Dhar’s two films remains unchanged. Pakistan is presented almost exclusively as a threat to India. Ranveer’s character, Hamza Ali Mazari, is revealed to be Jaskirat Singh Rangi, a convict (which, incidentally, connects Dhurandhar to Uri universe), who was given a chance at redemption through this high-risk assignment by Sanyal, the man at the centre of the mission. Those who argue that the film’s popularity or its technical finesse or its groovy music (by Shashwat Sachdev) invalidates criticism misunderstand the role of critique. A film that presents its worldview as synonymous with ‘patriotism’ leaves no room for disagreement without backlash.

The creative freedom debate

The wider context of Dhar’s creative choice takes us to the stream of films that have all received tacit support of the Centre. Vivek Agnihotri’s The Kashmir Files milked an immensely complex historical tragedy for a film so totalising that theatres became sites of communal sloganeering. Article 370produced by Aditya Dhar, cashed in on constitutional history, with the blessing of the political establishment and official endorsements before its release. Films like IB71, The Kerala Story, The Bengal Files, Kesari, Tanhaji, Swatantrya Veer Savarkar, Chhaava and others have similarly eyed emotional nationalism at the cost of contextual accuracy, using historical material as scaffolding for the ideological stand that suits the BJP and the RSS.

Also read: 120 Bahadur review: Farhan Akhtar’s India-China war drama finds its footing in parts

Cinema is a public art form. It enters cultural imagination and is consumed collectively by masses. When popular films consistently present a distorted version of events and foment hatred against a country or a community, the line between an external enemy and an internal “other” becomes dangerously thin. Such films only reinforce everyday prejudice against Muslims: at workplaces, in neighbourhoods, on social media.

When a film engages with real political contexts — national security, geopolitical conflict, nations and communal identity — it ought to be prepared for scrutiny about how it frames them. Artistic freedom is non-negotiable. Filmmakers must have the liberty to tell stories, to dramatise conflict, to express perspective. But freedom does not absolve responsibility. In the coming weeks, Aditya Dhar may well rake in crores, notching up the kind of commercial success producers dream of. But box-office arithmetic is of no help in moral accounting. However, with the film’s sequel, promising a larger role for Madhavan’s Doval and Ranveer Singh’s full-blown vendetta, planned for early 2026 release, the commercial rewards are likely to be too substantial for Dhar to pay much heed to what his critics have to say.

With time, one hopes, Dhar and his ilk realise the folly of what they are doing. A filmmaker who chooses to tell a certain story merely to please power, who draws on living histories only to sand them down into an instrument of propaganda, cannot plausibly argue that his conscience is clear. When a filmmaker keeps narrowing what his cinema is willing to imagine or confront, talk of artistic integrity rings hollow. In times like these, when power is eager for cultural validation and applause arrives easily for those who oblige, the real test of a filmmaker is not how well he rides the moment, but whether he resists it. On that count, commercial success offers no alibi.

Comments are closed.