Economy: The top 10 trends of 2025

The American economy today is just under 30% of the global economy, said Sharma.

Prannoy Roy: Hello and welcome to dekoder.com. If there’s one show on the economy and what lies ahead, it is this annual program with investor and writer Ruchir Sharma.

We will look at the 10 major factors that will affect each one of us in 2025, the research and insights for which are those of Ruchir and his team.

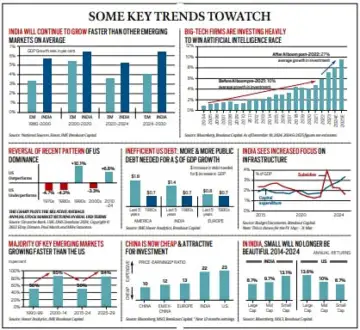

You start with the biggest trend – that there’s going to be a reversal in the recent pattern of American dominance. America is said to underperform the rest of the world. It’s overperformed the rest of the world by 6.6% per year for the last 15 years. Give us two or three reasons for it.

Ruchir Sharma: This trend is very extended. The American stock market’s outperformance has been going on really on a trend basis for 15 years. If you look at the historical pattern, typically when the American stock market does well in one decade, then in the subsequent decade, it at least gives back some of the gains.

We’re halfway through this decade, the American stock market has been way outperforming the rest of the world. The American economy today is just under 30% of the global economy. But the share of the American stock market in global indices, like the MSCI Global Index, is now approaching 70%.

It’s almost suggesting there’s no other country in the world worth investing in. And this has been boosted a lot with the fact that the dollar has been so strong, and that you’ve had tech companies in America earning extraordinary profits. Trump’s victory has given a further boost to this because there’s a feeling that if he imposes tariffs, it’s going to be good for America and bad for the rest of the world.

But this has become such a group-think and I’m very wary… In my 30-odd years of watching markets and investing, I’ve never seen such a strong group-think, which is that everyone expects America to be the only place to invest. This trend could reverse itself for reasons including America’s fatal flaw, its fiscal deficit, and also this economic concept of creative destruction…

Roy:Could you expand on this TINA – there is no alternative – factor that investors are mesmerized by?

Sharma: There is a feeling among investors that Europe is in bad shape. Japan is still facing such a big demographic challenge. Emerging markets in general are too small or too insignificant to invest in. China has not been doing well. There’s so much money sloshing around and if there’s any place we want to put this capital in, it’s only America.

Key trends to watch out this year

Roy:If you look at the top 10 firms in the world, there’s been massive churn for decades. But there’s been no churn in the first five years of this decade. It is dominated by American companies. Now you’re saying there’s going to be a churn and American companies will not dominate as much.

Sharma: This domination seems to have reached a peak. These companies have now become household names and they’re in a way basic essentials, whether it’s Apple, Amazon or even Google, Facebook.

But there are the laws of creative destruction, which is that new companies are supposed to come and take the place of old companies. Otherwise, the same companies will keep dominating, which is not the way capitalism is supposed to function.

In the last five years, the same companies that ended the decade dominating are still at the top; in fact, their dominance has only increased in the last couple of years.

But I feel they’re sowing the seeds of their own demise by spending so much on AI, and the returns may not be commensurate. I see the trend of group-think [of TINA] shifting this year.

Roy:Fiscal deficit is in a league of its own in America. It’s been 8% of GDP for this decade on average. It’s twice as high as Europe, higher than India, and almost twice as high as other emerging markets. That is a fatal flaw.

Sharma: In the last three to four years, America seems to have just blown past all historical records on fiscal deficit. It’s been able to get away because it has the world’s reserve currency. It’s able to print as many dollars as it takes. And because of the AI mania, people are willing to fund these deficits, saying that they have no other place to go.

Roy:The US debt is highly inefficient. It uses more and more public debt to achieve just one dollar of GDP growth. It used to be 70 cents to get one dollar growth. Now it’s 1.8 dollars to get one dollar.

Sharma: Yeah, the American economy has done so much better also because of the amount of debt it’s taken up. What exactly is public debt? It’s the government which is spending a lot. Just look at the number of jobs now being created by the government in America. This is supposed to be a capitalist economy and now nearly 20% of all jobs being created in America are being created by the government.

It shows you the role of government, how it’s increased… More than 50% of the counties in America are now reliant much more on transfer payments from the government. That number used to be not even 25% a decade or two ago.

Roy:So now Trump and Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy will change all this and cut down government jobs?

Sharma: We don’t know how much they’ll succeed. A lot of this government spending is on very sensitive areas like Medicare and social security benefits; very hard to touch.

Probably more importantly, even if they succeed, at least in the short term, it will mean that American growth could take a hit because it’s being artificially boosted today by so much government spending. Will they have the appetite to stomach that? And for how long? So, no matter which way you cut it, I think America will look less exceptional in 2025.

Roy:In India, capital expenditure infrastructure has gone up and subsidies have gone down. That’s a key aspect of growth.

Sharma: Even though India has always run a very large fiscal deficit, at least it’s stabilized. The fiscal deficit hasn’t increased much in the last decade or so, particularly at the Centre. The government is spending much more now on capital expenditure and less on subsidies. Although state governments in India are spending a lot more now on welfare, broadly, if you look at the picture over the last decade, the fiscal situation seems relatively calm and better managed with more spending towards productive stuff, which is infrastructure, and less on subsidies and welfare.

Roy:Now, moving to your fourth point, you’re saying that the share of key emerging markets is growing faster than the USA.

Sharma: When I wrote my first book, Breakout Nations, a decade ago, there was so much hype about BRICS and emerging markets, and I tried to caution that expectations are very high and these emerging markets may disappoint. And the true breakout nation may end up being America.

In the last decade, in many of these emerging markets, economic growth disappointed. Even in India, compared to what was expected, economic growth didn’t come out to be as strong. It’s plateauing now at around 6-odd per cent, but 10-12 years ago, everyone thought that India’s birthright was to grow at 8%.

I think that in the next few years, and these are projections being also given by the IMF, economic growth in some of these countries may outperform on the upside. That’s because they have cleaned up a lot of the excesses that they had built when they had the boom years of the 2000s, plus they’re investing a lot more in infrastructure and other productive investments. Also, they’re not as reliant on fiscal stimulus as America is to grow. So as America sort of weans off some of this fiscal excess and stimulus, these emerging markets could shine more in the next few years.

Roy:All your data shows that India is growing faster than other emerging markets.

Sharma: That’s because our base is lower. The per capita income at $3,000 is much lower than other emerging markets on average, which is closer to about $8,000 to $10,000. But India’s growth lead will continue. There’s a very old formula I’ve used for the last 30 years – that whatever the emerging market average, we typically tend to grow about one and a half to two points faster. I expect that growth lead to remain intact in 2025.

Roy: Your fifth forecast is China is investable again. China is now cheap and attractive for investment. The price-earning ratio in China is 10 compared to India and the US, which are 23 and 22. We are twice as expensive as them.

Sharma: I remain structurally bearish on the Chinese economy. The debt and demographic factor haven’t been resolved. I still expect those to be a headwind.

On China’s growth rate, I’m always concerned when views become too one-sided. Everybody has become very bearish on China. Everyone is telling you the same theories… I’m trying to say that, it’s still the world’s second largest economy, still the second largest stock market, if you look at China, Hong Kong combined. And there are some companies there, what we call diamonds in the rough. If you objectively look at some of the companies in China, they are doing relatively OK. They have some cutting edge technology.

Roy: One company that you pointed out, that’s BYD. Basically, you’re saying China’s investable and some Chinese companies are very undervalued. The number of cars BYD has sold is 4 million compared to Tesla’s 1.8 million. And their market value is 100 billion and Tesla’s 1.2 trillion, that’s 12 times higher.

Sharma: This is just an example that there are cheap companies in China with good quality products. And you look at these stock prices, which have been pummeled. Some stocks, especially in the tech space, are down 70%, 80% in dollar terms. That’s my point, that there are diamonds to be found in the rough in China, even if you’re structurally bearish on the economy as I am.

Roy:You’re saying there’s overspending on AI, and that’ll hurt big tech firms. They used to spend an average of 10% a year for many years; now they’re spending an average of 27% investment in AI.

Sharma: There’s a massive amount of spend which is going on. Some of these companies, they’re called the hyperscalers in America – the Microsofts and the Alphabets and Facebook, etc., even Tesla – the amount they’re investing in this is quite incredible. These big tech firms in America have been making extraordinarily high profits, but if they’re going to spend so much on AI, some of those profits are going to come down. And investors and other people are going to ask, who’s going to benefit from this?

If you look at past such revolutions, whether it was the Internet revolution that took place in the 2000s, or the shale oil revolution, the established firms were never the big winners. In fact, the established firms end up spending a lot, but the consumer, or some new firms benefited.

Again, I think that AI is the future. It’s here to stay. I’m not debating that. I think it’s this entire triangulation, which is that you have a lot of hype being created by these hyperscalers who are spending so much on AI. And then you have expectations, which are very high. And yet, in terms of what the product is being able to deliver, that’s still taking a lot of time to materialize.

So therefore, I think that this could be something which could hurt the profitability of these big tech firms that are spending so much on AI.

Roy: You’re saying in 8 out of 10 forecasts that trade will grow without America now. Eight out of the 10 hottest trade corridors currently do not include the US.

Sharma: There are signs that this trend is likely to accelerate. We just saw the European Union signed a deal with a bunch of Latin American countries to bring tariffs down by 90%. Regional trade agreements are accelerating; bilateral trade agreements are accelerating.

If you look at the trade corridors around the world, the maximum growth is taking place between countries which don’t involve America. In fact, eight out of these 10 don’t involve America.

So the world is moving on – and when someone asks me how the world should adapt to a Trump world, my point is, start thinking about how to do things outside of America.

Roy:India has also signed, is signing, more regional trade agreements than before.

Sharma: There was a big hiatus. Last decade, India barely signed any new trade agreements. But in the last three to four years, that pace has accelerated. And these are trade agreements without America. With countries like the UK, Oman, trade agreements are being currently negotiated.

I wish we’d do more to trade with our neighbours, though. That remains one of India’s weaknesses – if you look at the big success stories around the world, including China, they have very good trading relationships with their immediate neighbours. Cost of transport is so much less, regional hubs are much easier to create, the synergies are much easier to create…

Roy: You’re also saying that private funding is going to slow down globally. Between 2000 and 2019, it grew from 1 trillion to 7 [trillion]. And from 2019 to 2024, in the last five years, it’s gone from 7 to 14.

Sharma: We were sort of conditioned to think about all funding mainly happening through public markets. But in the last 10-15 years, particularly after the global financial crisis, you’ve seen a big explosion take place in the private markets. One is private equity, which is where people take a stake in companies that are not listed on the stock market. Or even when lending happens, it takes place outside of the traditional banking system, on a private basis.

Roy: Your graph says private equity, from being well below public funding, has now overtaken public funding. Public capital is – 5% growth, private equity + 10%, and private equity from being way behind public is now ahead of public.

Sharma: I’m trying to say that a strength taken too far becomes a weakness, which is that this may have gotten a bit too far and now you’re seeing a lot of retail people wanting to participate in this. At the end of the day, if you throw too much money at something indiscriminately, there are negative consequences.

Roy:In India, private funding is growing fast, but still at an early stage. It’s only 120 billion right now.

Sharma: Very small. The global number runs in trillions of dollars. We are still not even running in hundreds of billions of dollars. Whether it’s private lending, private equity, whether it’s got to do with public markets in terms of their domination, it’s very US centric. I’m not that concerned about what’s happening in India as yet. But globally, I do expect the growth in private credit, in private lending and in private equity to slow down, particularly in the US.

Roy: Your final forecast is about obesity – that there is no magic solution. America is at a different level of obesity – 44% – about the highest in the world for any major country.

Sharma: And like nearly three times the global average. That’s why in America there’s also this big craze for finding a magic solution to this. Some of these weight loss drugs, for some people, are beneficial. But the whole idea [seems to be] that you can just sit there and pop Ozempic and keep popping ice cream as well. And watch television and don’t do any exercise.

Roy:Look at the massive increase in sales of obesity drugs, GLP-1, Ozempic and various others. From [$]3 billion four years ago to [$]24 billion now.

Sharma: My point is that there is no magic solution to this, it can’t be so simple. And how long can you sustain this and what side effects will you have?

Roy:You’ve got this interesting graph of the side effects. People who have side effects of various types are searching on Google what to do about it, and they’ve gone up by 300%.

Sharma: These drugs, for curing diabetes and other stuff, they’re very beneficial. But to expect that we have found the magic drug, I’m very suspicious of that.

Studies show that when you are on these drugs for over a year or so, you can expect your weight to come down possibly on average of around 18%. But the moment you give it up, then your weight starts to go back up and your net weight loss is closer to 5-6%. Not 18-20%.

Edited excerpts from the conversation on deKoder, presented in collaboration with The Indian Express. Ruchir Sharma is the founder of Breakout Capital and the chairperson of Rockefeller International. He is a contributing editor of the Financial Times and author of several books, including What Went Wrong with Capitalism (2024).

Comments are closed.