Freedom: Vietnamese school children escape grade pressure overseas

One evening in September 2023 in Turku, Finland, Nga, 37, was braced for slogging through her 10-year-old daughter Han Dong’s homework like they used to in Vietnam.

To her surprise, Dong took just five minutes to complete four simple time-counting exercises.

“At first I thought my child was being lazy, but in reality she only has one very small homework task each day, mainly to review what she has learned and prepare mentally for the next lesson,” Nga, who herself is currently studying early childhood education in the northern European country, said.

This trip will be 2025. |

Now, after two years there, Nga has come to appreciate the “less is more” philosophy that has helped keep Finland’s education system among the world’s best.

Students are not ranked or compared. Assessments are designed solely to identify each child’s abilities and pinpoint areas where support is needed, which schools provide promptly and free of charge.

In Finland, early childhood education is a public service aimed at fostering learning through activities, interactive play and exploration.

Six-year-olds get a year of pre-primary education before entering first grade, with schedules centered on play-based and experiential learning.

Compulsory education lasts nine years, and only at age 16 do students sit a national standardized exam to choose between academic and vocational pathways.

To sustain a “pressure-free” system, Finland relies on teachers recruited from the top 10% of university graduates, all of whom must hold a master’s degree. Teaching is a highly respected profession, on par with doctors and lawyers.

Dong’s teacher told Nga: “We believe children should go to school with joy. When they feel happy, learning is more effective.”

Dong currently attends four to five classes a day. Subjects such as environmental studies, science and even mathematics often take place in forests or parks near her school.

“About 75% of Finland is forest, and so nature becomes the second classroom,” Nga says.

“Rain, wind or even minus-20-degree snowstorms don’t stop the children from going outdoors.”

The open environment helped Dong integrate quickly. After the first week she called her grandparents in Vietnam to say: “I like going to school here more.”

That sense of being unshackled is also familiar to Ngoc Diem, 26, who moved to Australia with her child two years ago.

|

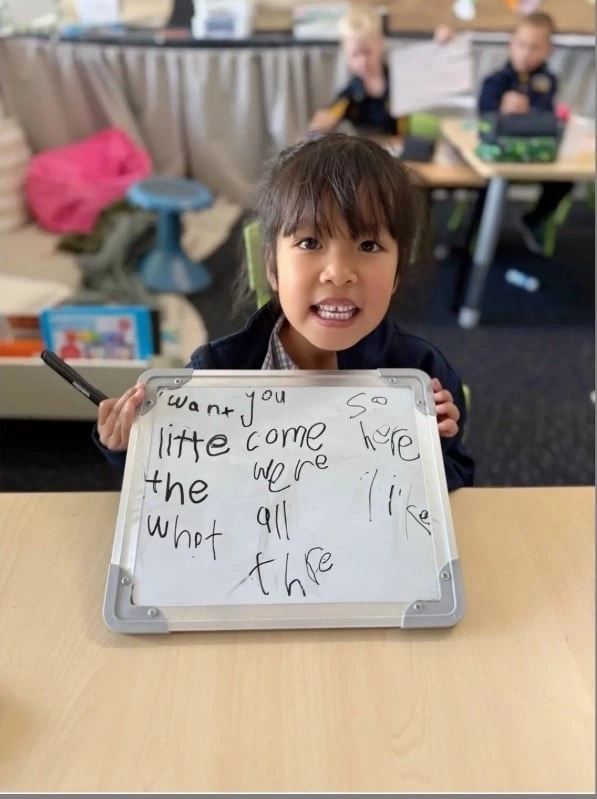

Ngoc Diem’s six-year-old daughter during a school session in Australia, November 2025. Photo courtesy of Diem |

The family’s decision to emigrate was partly driven by tearful mornings in Hai Phong, Diem’s hometown in northern Vietnam. Diem recalls a period when her daughter’s days began at 6 a.m. with a heavy backpack and ended at 11 p.m. at the study desk.

“Once I stood outside the classroom door, frozen, as I heard the teacher scolding my child in front of the class because her handwriting did not align properly with the lines,” she says.

The pressure pushed the six-year-old into crisis, making her fearful of school.

In Australia, everything changed.

Her daughter’s school bag now holds little more than a lunch box. Classes are from 8:30 a.m. to 3:15 p.m., with almost no homework.

Instead of practicing handwriting hard, she learns swimming, technology and foreign languages. The mother’s habitual question “Did the teacher scold you today?” has disappeared entirely.

While Finland and Australia emphasize happiness and balance, the U.S. education system helped Tran Thanh Thao, 60, solve the puzzle of “personalized learning” for her daughter, Thu Ha.

Thao still shudders when recalling her daughter’s time at a school for gifted students in Hanoi in 2010. Although the family did not pressure her, the 13-year-old imposed intense expectations on herself to keep up with classmates.

Every evening Thao would rush back and forth with her daughter to extra classes until exhaustion.

Watching her child stay up late memorizing knowledge, Thao often wondered: “Does this way of learning really lead to a better future?”

A work transfer to the U.S. changed everything. The credit-based system allowed students to design their own academic pathways. Noticing Ha’s fast learning pace, the school permitted her to sit exams to skip grades, moving directly from Grade 7 to high school and enrolling in advanced classes.

Freed from rigid age-based progression, Ha surged ahead. At 15, while peers in Vietnam were preparing for high school entrance exams, she had already graduated and received a full university scholarship.

Through dual enrollment, she completed a master’s degree at just 18.

Reflecting on her daughter’s rapid progression, Thao says it was not a miracle by a prodigy, but the result of an education system that avoids forcing students to study too many subjects unrelated to their strengths or imposing performance pressure.

“Without moving to the U.S., my child would never have dared to make any breakthroughs.

“She transformed from a girl afraid of making mistakes into someone confident, who knows clearly what she wants.”

|

Han Dong walks to school in Turku in 2024 (L) and paints a lakeside landscape in Lapland in Finland in summer 2025. Photo courtesy of Nga |

The stories of Nga, Diem and Thao are not one-offs.

Whether moving abroad for education, migration or work, they represent a growing number of Vietnamese scouring for more suitable learning environments for their children.

A 2024 report by SEVIS (the U.S. Student and Exchange Visitor Information System) shows Vietnam now ranks second globally in the number of K–12 students (students in kindergarten to Grade 12) studying in the U.S., behind only China.

The data underscores a rising trend of education-driven migration at earlier ages rather than waiting until university.

A 2024 survey by BritCham Vietnam also found that 49% of Vietnamese parents want their children to pursue international programs to develop holistic skills, critical thinking and independence rather than focus solely on grades.

Whether it is studying less to be happier in Finland and Australia, or accelerating toward success in the U.S., what unites these families is a shared search for environments that respect individual differences.

“Education should not be about molding identical forms,” Thao concludes.

“It should be about creating the most suitable soil for each seed to grow naturally.”

Comments are closed.