Portrait of a superstar of Hindi cinema who became his own genre

Six days before his 60th birthday, Salman Khan posted a series of gym images on social media showcasing a sculpted, muscular physique that belied his age, captioning them with a wry nod to the upcoming landmark moment in his life: “I wish I could look like this when I am 60! 6 days from now…” Fans, in awe, flooded comment threads with admiration. “Age-ing like fine wine…but with biceps that can bench-press time itself,” wrote a fan on X. It was a fitting prelude to the birthday chatter in the days that followed.

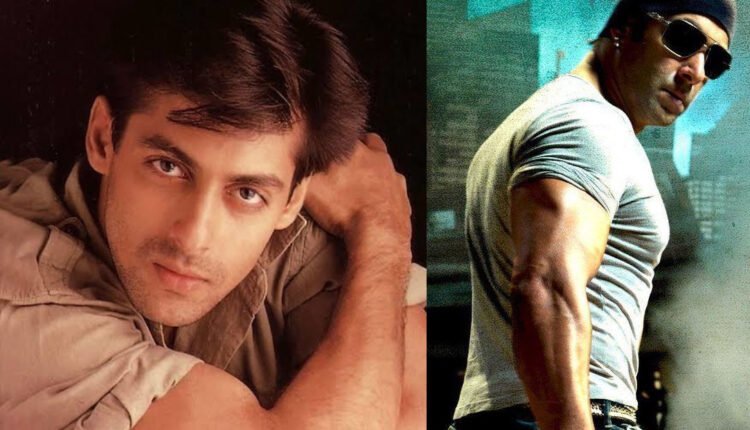

The pre-birthday gym drop — that playful taunt at the calendar by the star who was recognised as one of the world’s most handsome men in 2004 by People Magazine — goes in sync with the arc Mohar Basu sketches in a new, unauthorised biography, Salman Khan: The Sultan of Bollywood (HarperCollins India). She traces the shift from the shy 90s charmer to the broad-shouldered, “bull-like” figure. She writes: “Over the years, we have seen Salman’s walk morph from boyish and casual to intense, bull-like. We have seen him become a myth. And, like all myths, he means different things to different people.”

Basu adds that the audience can no longer be sure which Salman they are meeting — the romantic Prem, the vigilante cop, the cranky host on weekends of Bigg Boss, or the benevolent hero who insists on righting wrongs with his chest first and logic later. In those gym pictures, in the fan frenzy that followed, you can see that myth still functioning: a superstar refusing to age into nostalgia.

Helping people escape their realities

The author recounts watching Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015) at Mumbai’s Gaiety Galaxy, the crowd erupting as if participating in a collective ritual. “Salman’s brand of cinema erases the lines that reality draws in our lives. It builds bridges where others draw borders… It is not interested in subtlety. It believes in gestures so loud that they drown out everything else.” It is the kind of description one cannot apply to most Bollywood actors at 60 without sounding sentimental. With Salman, it sounds empirically correct.

This unconditional adoration is what has kept him in circulation as an actor for nearly four decades and what makes his 60th year feel less like another chapter or act about to begin. In the last one decade since Bajrangi Bhaijan, he has done many more films, including Sultan (2016); Tubelight and Tiger Zinda Hai, both of which released in 2017; Race 3 (2018); Bharat and Dabangg 3 (2019); Radhe: Your Most Wanted Bhai and Antim: The Final Truth (2021); Kisi Ka Bhai Kisi Ki Jaan and Tiger 3 (2023). A mix of hits and absolute duds.

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan: The King of Bollywood who wears humanity like a second skin

Currently, Khan is preparing for one of the most consequential films of the next stage of his career, Battle of Galwan, a war drama based on the 2020 Galwan Valley clash. Shooting for the film has wrapped under director Apoorva Lakhia, and the first look or teaser has been planned as a birthday release gift to fans on December 27.

Tracing the reason behind his massive fandom, Basu writes: “There is a reason why Salman is worshipped by middle-aged uncles and college kids, by aunties and neighbourhood dadas, by autowallahs and doctors alike. You do not aspire to be him, but you are inspired by him. He helps people escape their realities into glorious worlds where they can do what’s right, what everyone says is impossible, all within the confines of a dark cinema hall.”

Return of the superstar

Salman turns 60 with the sort of news cycle only he can command. On one side, photos from the Panvel farmhouse: family, cricketers, actors, directors turning up for a midnight celebration. On the other, court dates and legal analysis of a poaching case that refuses to die, with the Rajasthan High Court still hearing appeals around his 2018 conviction in the blackbuck matter. It is a neat summary of Abdul Rashid Salim Salman Khan’s public life: megastar, entrepreneur, fundraiser, repeat offender in the eyes of activists, permanent TRP machine, and still among the Hindi film industry’s most reliable actors.

Born in Indore on 27 December, 1965, to screenwriter Salim Khan and Salma (formerly Sushila Charak), Salman was raised in Mumbai in the shadow of his ‘hot-headed’ screenwriter father, of Salim-Javed fame. “The silent, temperamental, explosive parent is a large part of who he is,” writes Basu. Salman made his debut as a supporting actor in Biwi Ho To Aisi (1988). A year later, Maine Pyar Kiya turned him into a wall-poster romance hero and a middle-class crush for the late-80s: lean, awkwardly earnest, happy to sing in garages and fight goons in stone-washed denim. By the mid-90s, Saajan, Hum Aapke Hain Koun..!, Karan Arjun, Hum Saath-Saath Hain and Andaz Apna Apna had fixed his place in the Hindi film imagination: the affable lover-boy who could also throw a punch, dance at weddings and crack deadpan jokes.

A still from Bajrangi Bhaijaan

After Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999) — his only full-length film opposite Aishwarya Rai during a period when their off-screen relationship was headline material — Salman moved into the early 2000s with a series of superhits and flops like Tere Naam (2003) and Phir Milenge (2004). In Tere Naam, his iconic, long-haired look, with his locks falling over his forehead — inspired by former President Dr APJ Abdul Kalam — captured the rebellious, small-town hero image of his character Radhe in love, truly, deeply and madly.

But these highlights were surrounded by long spells of inconsistent projects and relentless tabloid attention. Two cases in particular reshaped his public life and media image: the 2002 hit-and-run incident in Mumbai, in which a pavement dweller died, and the 1998 blackbuck poaching case during the shoot of Hum Saath-Saath Hain (1999). Legally his position remains in a grey zone: he was acquitted by the Bombay High Court in the hit-and-run matter, while in the poaching case he was convicted and handed a five-year sentence in 2018, though currently out on bail as appeals continue before the Rajasthan High Court with the possibility of further proceedings.

Also read: Saif Ali Khan: The curious case of Hindi cinema’s gentleman rogue

After a stretch of films that underperformed or garnered mixed responses in the early 2000s, it was Prabhu Deva’s action film Wanted (2009), a Hindi remake of the 2006 Telugu hit Pokiri with punchy set pieces and high-octane energy, that reinvigorated Salman’s bankability as an action star, paving the way for his subsequent string of blockbusters including Dabangg, Ek Tha Tiger and Bajrangi Bhaijaan.

The blackbuck case has, in recent years, become the albatross around Salman’s neck. Gangster Lawrence Bishnoi’s antipathy toward the actor traces back to the poaching case only since the Bishnoi community considers the blackbuck as sacred and holds Salman responsible for the alleged hunt. In April 2024, unidentified gunmen opened fire outside Salman’s Bandra residence, with police linking the suspects to associates of Lawrence’s network, and in2025 members of the Bishnoi gang publicly warned that anyone — actors, directors or producers — working with Salman could be targeted, even claiming responsibility for shootings at comedian Kapil Sharma’s café in Canada after an invitation to Salman. Salman has publicly responded by saying life and death are in higher hands, and his security detail has been strengthened in response to these threats.

The transition from Prem to Bhai

If you had to track Salman’s career by one name, it would be “Prem”. For Sooraj Barjatya’s Rajshri banner, he was the boy-next-door avatar of a conservative, aspirational India – Prem in Maine Pyar Kiya, Prem in Hum Aapke Hain Koun..!, Prem again in Hum Saath-Saath Hain and later Prem Ratan Dhan Payo. By the late 2000s, though, the Rajshri universe had faded and multiplex Hindi cinema was flirting with realism, noir, urban drama.

Salman’s response was to move in the opposite direction and invent a new screen creature: the swaggering cop/gangster/agent with a punchline for a surname. So, a year after Wanted, came Dabangg (2010), in which he played Chulbul Pandey, the belt-spinning and moustache-twirling cop. The same decade gave him Ready, Bodyguard, Ek Tha Tiger, Kick, Bajrangi Bhaijaan, Sultan and Tiger Zinda Hai. At one point, Salman had a run of nine-plus consecutive films crossing Rs 100 crore in India, something no other Hindi star had managed.

The industry’s logic was simple: a Salman release on Eid became a quasi-religious ritual of its own, particularly in North and West India. The films mixed South-style action, broad comedy, chest-thumping songs and a dose of moral reassurance. In Bajrangi Bhaijaan, which grossed around Rs 969 crore worldwide and won the National Award for popular film, that reassurance meant an India-Pakistan fairytale about a Hanuman bhakt smuggling a lost Pakistani child home. In Sultan (2016), it meant a wrestling epic about humiliation and redemption. In the Tiger series, it meant a globe-trotting RAW agent who keeps saving the subcontinent from disaster, shirt and geopolitics both ripped in slow motion.

The forever bachelor

Since 2010 Salman has been the face, ringmaster and sometimes moral science teacher on Bigg Boss, turning a reality show about squabbling participants into a weekly referendum on his own whims. The set is his court: he scolds, consoles, cracks innuendo, occasionally tears up. In return, the show gives him constant exposure to an all-India audience that may or may not buy a ticket but will certainly watch Colors, and now JioHotstar, on a weekend. This TV persona feeds the meme universe that surrounds him: the walk, the bracelet, the deadpan delivery.

At the same time, his logistics suit the economics of post-single-screen India. Distributors know that a “Salman film” – especially on Eid – guarantees strong opening figures almost regardless of reviews. Exhibitors in small towns still speak of him as a bankable bet when everything else looks uncertain. During the 2010s, when many mid-budget films struggled to survive one week, his films were running house-full shows even after brutal critical drubbings.

Post-pandemic, that equation has been more fragile. Radhe bypassed theatres almost entirely with a hybrid digital release. Kisi Ka Bhai Kisi Ki Jaan and Tiger 3 opened well but underperformed relative to earlier peaks, especially when compared to the wave triggered by Shah Rukh Khan’s Pathaan and Jawan; SRK, incidentally, too, turned 60 this year on November 2. For the first time since the Dabangg era, the industry has had to ask: is the “Bhai + Eid” formula enough, or does the content finally have to work harder?

In 2007, Salman launched the Being Human Foundation, which funds education and healthcare initiatives; the clothing line of the same name, started in 2012, funnels a part of its profits back into the trust. Walk through any North Indian mall and the logo – a hand-drawn heart – still pops out from store façades and T-shirts. For fans, it reinforces an old belief: that he is “dil se achha (good-hearted)”, whatever his flaws. For critics, it is brand management with a charity ledger attached. Both can be true at once.

A still from Ham Dil De Chuke Sanam

His relationships — from Sangeeta Bijlani and Somy Ali to Aishwarya Rai and Katrina Kaif — have been analysed and pored over to death, with the Aishwarya episode in particular shadowed by allegations of abuse. He has never married, which, if anything, has only added to his strange, extended adolescence as a public figure: permanently between boyfriend and bhaijaan, muscle-packed 20-something on screen long after his co-workers have made peace with the roles of fathers and mentors. Salman’s defenders argue that he has been singled out because of his fame; his detractors see the cases as proof that the system ultimately bends around money and influence.

Acting, or something like it

One persistent accusation against Salman is that he “doesn’t act”. The allegation is half-fair and half lazy. It is true that in a large chunk of his filmography, especially the more recent action vehicles, he operates on auto-pilot: the same smirk, the same fight choreography, the same shirt-ripping climax. At the Red Sea Film Festival in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Salman modestly admitted that he doesn’t see himself as a great actor. “..Mujhe nahi lagta ki main koi bahut hi kamaal ka actor hoon (So I don’t think I’m a particularly amazing actor). You can catch me doing anything, but you can’t catch me acting,” he said, adding, “Woh hoti hi nahi mujhse. Jaisa feel hota hai, waise karta hoon. Bas yahi hai. (Acting doesn’t happen to me at all. I just do what I feel like doing. That’s all.)”

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan at 60: The last of the superstars, who has taught India how to love

But scattered across the decades are performances that complicate his own statement about acting. Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam gives him a controlled, wounded dignity as the husband who realises he is the understudy to his wife’s great love — and then decides to help her chase it anyway. Tere Naam’s Radhe is troubling both for the film’s treatment of stalking and for the rawness he brings to the character’s breakdown. Phir Milenge uses his star power to normalise an AIDS patient in mainstream Hindi cinema, something the WHO explicitly acknowledged at the time. Bajrangi Bhaijaan is perhaps the cleanest demonstration of what he can do when he surrenders to a strong script and director. As Pavan, he plays a man of limited intelligence but vast moral stubbornness; the performance is loose, warm, often very funny, and surprisingly free of the vanity that marks his more recent work.

A still from Maine Pyar Kiya

Some of his films show an instinctive performer who can land emotion cleanly when he wants to. The rest of the time, he is less actor and more of a star. Hindi cinema has always accommodated performers who operate on this wavelength: Dara Singh, Dharmendra, early Dharmendra, even bits of Rajinikanth’s later Tamil work. The performance is in the aura, not in the method or the modulation. Once you accept that, the films look different; they are not about interiority but about watching a familiar body do familiar things in unfamiliar locations.

What does 60 look like from here?

At 60, Salman knows, Hindi cinema is at crossroads. Shah Rukh Khan has just enjoyed a massive second inning with Pathaan and Jawan and younger stars like Ranveer Singh has just tasted Rs 1000 crore-success with Dhurandhar. The Hindi film audience is increasingly happy to jump ship to Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu or Korean content if Bollywood bores them. Salman’s recent line-up reflects that uncertainty. The most intriguing promise in his upcoming slate is Tiger vs Pathaan, positioned as the marquee crossover in the YRF Spy Universe — the arena where Ek Tha Tiger, War and Pathaan built their muscle. It brings Salman’s Tiger face-to-face with Shah Rukh Khan’s Pathaan in what is intended as a full-scale confrontation, directed by Siddharth Anand.

Future announcements, including rumours of Bajrangi Bhaijaan 2, suggest more of the same: high-concept action, familiar branding, calibrated risk. The question is whether he will allow himself another left turn: a smaller film, a genuinely self-aware part, or a quiet, age-appropriate drama. There is also a generation of younger actors and producers who grew up worshipping him, now powerful enough to pitch new kinds of projects. If he listens to them, there is scope for an interesting late-career reinvention. Off screen, Salman has the foundation to grow, the clothing line to manage, the TV presence to maintain and the court cases to navigate.

Sixty is supposed to be an age of retrospection, a gentle fade-out. Salman’s 60th looks more like another interval: the lights are up, the audience is restive, there are murmurs about whether the second half will be worth it — and somewhere in the wings, the man the masses hanker to see is still doing push-ups, still rehearsing that familiar walk towards the front of the screen.

Comments are closed.