Vietnamese students face visa hurdles as countries tighten rules

Le Tran, 27, recalls her despair after receiving a visa rejection message from the Australian embassy a few months ago after she had prepared for over a year.

She says even staff at student visa consultancy agencies are surprised by the wave of rejections Vietnamese students faced.

“I was still crying a month later. If they had at least interviewed me and I had failed, I wouldn’t have felt as upset as not even being called for an interview.”

Major study destinations like Australia, Canada and the U.K. have tightened student visa requirements, citing concerns over overstaying students, housing pressure and questionable intentions.

This has led to higher rejection rates, affecting students like Tran, who, despite a well-prepared application and substantial financial proof, was denied a visa.

She says: “A monthly salary of around VND15 million (US$590) seemed reasonable for my age and the city I live in, making it possible for me to consider studying abroad. Everything was prepared legally according to Australian law.”

Her lawyer had submitted a financial report to the embassy along with proof of over VND1 billion in her savings account, but she was still refused a visa.

Her experience is similar to that of many Vietnamese students, who face unexpected rejections, sometimes without even an interview, as embassies apply tougher criteria.

They claim it is in response to students overstaying or using study visas as a pathway for migration rather than education.

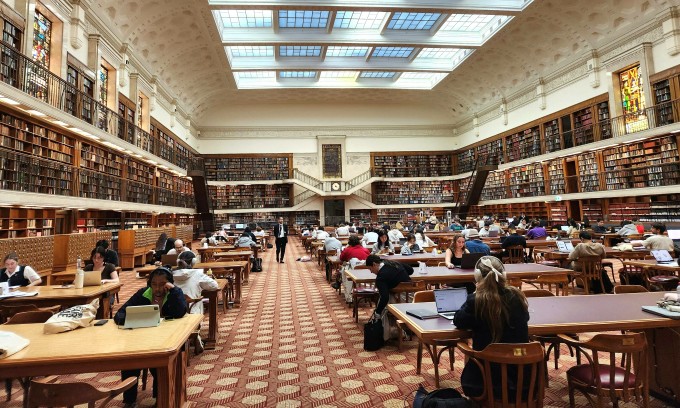

Students attend the New South Wales Education Expo Vietnam 2024 in Hanoi, Sep. 10, 2024. Photo courtesy of the organizer |

In February Australia reduced the post-study work period for international students from four to six years down to two to four years.

Universities were also categorized into three groups based on “risk”, with visa processing times slower for those in the two lower levels.

In March Australia also raised the minimum English requirement for international students by 0.5 points to an IELTS score of 6.0–6.5, and brought in a new cap for part-time work of 24 hours per week.

It increased the financial proof requirement by 20% to AU$29,710 (US$19,820).

In a similar case, Thanh Truc’s application to study in Australia was rejected early this year when student visas were less difficult to obtain.

“When I received the rejection letter, I was shocked,” she says.

She says her application was rejected just a day after receiving confirmation it was being processed: “It was that fast—they didn’t even bother reviewing it.”

Truc believes the rejection may have been due to her nationality and the lower-level program she applied for.

Vietnam’s passport has recently slipped three places to 90th on the Henley Passport Index, with visa-free access to 51 out of 227 destinations, down from 87th and 55 destinations.

At a study abroad seminar in Hanoi on March 31, experts spoke about challenges major education destinations face, including an influx of “fake students” and pressure on housing and infrastructure, leading to tightened policies for international students.

Reflecting on her application process, Tran says visa restrictions began intensifying last year, peaking in early 2024 due to concerns over overstaying students.

“When I looked at groups online, it seemed like everyone was being denied a visa, no matter their profile or financial standing.”

Despite holding an Australian student visa, another student, Ngoc Tran, was denied a tourist visa to New Zealand due to concerns she might not return to Australia.

“Holding a Vietnamese passport has certain disadvantages,” she says.

“I applied for the New Zealand visa while my Australian student visa was valid until 2028. I could prove my income and savings.”

According to recent education data from consultancy firm Studymove and Australian government statistics, Australia granted 298,000 student visas between October 2023 and August 2024, marking a 38% decline year-over-year.

Visas issued to Vietnamese students decreased by 28%, with the Australian Department of Home Affairs frequently citing “dishonest study purposes” as a reason for rejection.

The vocational education sector saw the largest impact, with visa issuances declining by 67%, while visas for English language courses and higher education reduced by 50% and 25%.

Other countries also experienced declines, with visas declining by 67% for Filipinos, 62% for Colombians and 56% for Indians.

The Department of Home Affairs said Vietnam has risen to the top six in terms of the number of study visa applications, increasing from 18,700 in the 2022-23 academic year to over 24,400 the following year. Approval rates dropped from 91% to 76%, the lowest in 18 years.

Speaking at the 2024 New South Wales Education Showcase in Vietnam in September, Katherine Tranter, senior migration officer at the Department of Home Affairs, said the decline in approval rates aligns with a broader trend affecting the top countries sending students to Australia.

She listed six common reasons for visa rejections: incomplete documentation, failure to respond to additional information requests, dishonest study intentions, document fraud, failure to meet English language requirements, and insufficient proof of finances to meet studying and living expenses.

“The most common reason is dishonest documentation. We will refuse an application if it lacks a genuine admission letter or if the documentation suggests the applicant is not a genuine student.”

Nhu An Lam Duc, academic director at MoraNow, a platform providing consultancy for Vietnamese students seeking overseas education, says: “The government’s stricter visa policies for Vietnamese students directly respond to the high number of students who stay in Australia rather than returning. This has impacted the reputation of Vietnamese people abroad.”

Previously students with genuine intentions could secure a visa more easily, but now higher demands and stricter requirements have become obstacles, even for financially capable applicants, she adds.

Lu Thi Hong Nham, director of Duc Anh Overseas Study Advisory & Translation Co. Ltd, says: “Australia’s government is clearing out to make room for serious, capable students.”

She advises students to consider factors like post-graduation job prospects and career goals when deciding to study abroad.

Nguyen Thanh Sang, regional director for Vietnam and Singapore at IDP Education, says new policies in the U.K. and Australia refocus international students on the primary goal of studying.

He suggests that students should explore alternative education destinations and that the education system should diversify study-abroad options to give them more choices.

In response to the restrictions, some students like Tran are considering vocational studies in countries like Germany.

Tran says studying in Germany is more affordable, allows for practical experience and opens up opportunities across Europe, offering a hopeful alternative amid tightening visa conditions.

Comments are closed.