Why scientists say jupiter may be slightly smaller than earlier estimates

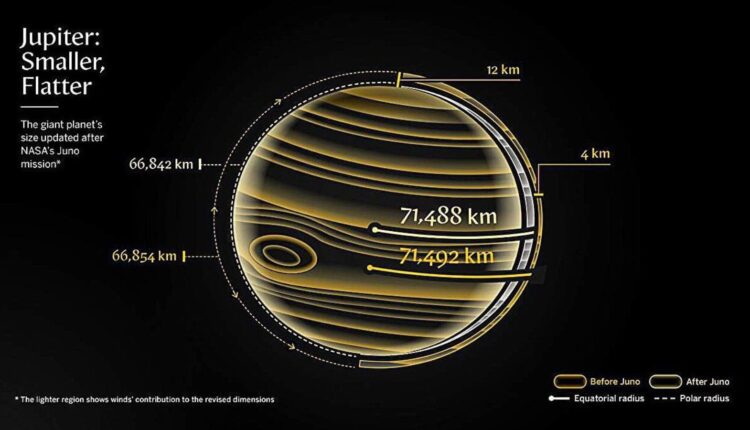

Scientists report that the solar system’s biggest planet is slightly slimmer than past estimates, thanks to more precise readings from Nasa’s Juno spacecraft. Regarding Jupiter, scientists who have studied our solar system’s largest planet have come to a new realisation: it may not be as massive as previously thought. In fact, Jupiter seems to be slightly thinner and flatter. While the change is small, the discovery offers fresh insight into the planet’s structure and behaviour.

The findings were published on February 2 in the journal Nature Astronomy. Even with the revised measurements, Jupiter remains the largest planet in the Solar System by a wide margin.

For decades, Jupiter’s size was based on data from Nasa’s Voyager and Pioneer missions, which flew past the planet nearly 50 years ago. Those spacecraft employed a technique known as radio occultation. In short, they transmitted radio signals through Jupiter’s atmosphere. These signals were then sent back to Earth. The bending of the signals was studied to figure out the approximate size of Jupiter.

However, researchers now believe these early estimates did not adequately account for Jupiter’s powerful winds. Jupiter’s winds are so strong that they can distort its atmosphere. This distortion can affect the transmission and reception of radio signals.

What Juno brings to the table

Nasa’s Juno spacecraft, which has been in orbit around Jupiter since 2016, offered a chance to reassess these figures with much greater detail. Researchers analysed 24 new radio occultation readings taken during a newer phase of Juno’s mission, when the spacecraft passed behind Jupiter from Earth’s viewpoint.

“When the spacecraft moves behind the planet, its radio signal bends as it passes through the atmosphere,” said Scott J. Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator, in a Nasa statement. “This gives us a very precise way to measure Jupiter’s size.”

Based on the new analysis, Jupiter measures about 83,067 miles from pole to pole and 88,841 miles across its equator. That makes the planet roughly 15 miles shorter at the poles and about 5 miles slimmer at the equator than earlier estimates suggested.

While those differences may seem tiny for a planet of Jupiter’s scale, scientists say they matter.

Why the change matters

Experts say the updated size helps them better understand what is happening deep inside Jupiter. “It’s not just about knowing the exact radius,” said planetary scientist Oded Aharonson, who was not involved in the study. “It helps us build better models of the planet’s interior.”

The new measurements are already improving how well scientists can match Jupiter’s gravity data with observations of its atmosphere. Because Jupiter is often used as a reference point for studying giant planets beyond our solar system, the findings could also help scientists better understand gas giants elsewhere in the universe.

Comments are closed.